I’ve been winding down these last few evenings with a real treat: Benjamin Radford’s new book Scientific Paranormal Investigation. I expect to tackle a full review soon; for now, I’m getting a kick out of his unapologetic pitch for serious skeptical scholarship. It’s a topic I think about often, but rarely more than right this second — staggering as I am under the weight of my own current research.

I’ve been winding down these last few evenings with a real treat: Benjamin Radford’s new book Scientific Paranormal Investigation. I expect to tackle a full review soon; for now, I’m getting a kick out of his unapologetic pitch for serious skeptical scholarship. It’s a topic I think about often, but rarely more than right this second — staggering as I am under the weight of my own current research.

How important is scholarship for skeptics? Should skeptics know a lot about the paranormal literature (or, rather, the many niche literatures for the many niche paranormal topics)? And, does it matter whether we know much about the literature of skepticism?

When I’ve asked these questions in the past, I’ve received mixed responses. Some skeptics argue that vast encyclopedic knowledge is essential. Others claim that traditional skeptical expertise is more or less irrelevant to modern skeptical activism.

That wide range of opinion arises from the many kinds of skeptics pursuing their many kinds of projects. Some, like Ben Radford, are serious primary researchers, dedicated science communicators, or both. They wish to solve mysteries and inform the public, and they necessarily care about refining the best practices for achieving those goals. Of course, not all skeptics share those interests or responsibilities. Some are satisfied to indulge their own curiosity, or to hone their own critical thinking skills. Others view skepticism as a social scene rather than a research project — a way to find friends who accept their science-informed worldview.

Finding Stuff Out

Still, I’d suggest this as a general principle: the more willing we are to express opinions on skeptical topics, the more seriously we should pursue skeptical scholarship. When we take on a public role (even if only a Twitter stream or blog) we take on an ethical responsibility to strive for accuracy.

Even simpler, the ethos of skepticism calls for active rigorous investigation. I usually let Mark Twain’s “old and wise and stern maxim” say it for me: ”Supposing is good, but finding out is better.”

In an important sense, the whole of the skeptical project over the past 35 years can be boiled down to that one single piece of advice. There’s no getting around it: finding out is better. I can’t think of any area of domain expertise where less knowledge is as good as more.

If we’re committed to finding out, then literacy in our field becomes very important indeed. It helps us to ask the right questions, and to avoid the wrong conclusions. As Radford explains,

Skepticism, like science or any other body of knowledge, works on precedent. Scientific paranormal investigators need not — indeed should not — approach a case without background information and having researched previous investigations. While the specific circumstances of a mystery may be unique in each case, the type of mystery is not. Any investigation, from aliens to zombies, monsters to mediums to miracles, has many earlier solved cases as precedents. … Researching and knowing the history of skeptical investigations into paranormal claims is not simply a matter of paying your dues; it is essential to conducting an informed investigation.

He’s right. When we consider pseudoscientific topics, it pays to know where they come from. The more we know about the roots of a mystery, its history and proponents and scandals and related claims and so on, the better (and more fair) our assessment is liable to be — and the better able we are to communicate responsibly about that topic. Moreover, the wider and deeper our general knowledge of pseudoscience, the better prepared we are to respond quickly to mutations of old ideas. (Bomb-detecting dowsing rods are a stark reminder that even the most harmless and hokey old chestnuts can reemerge in lethal new variants.)

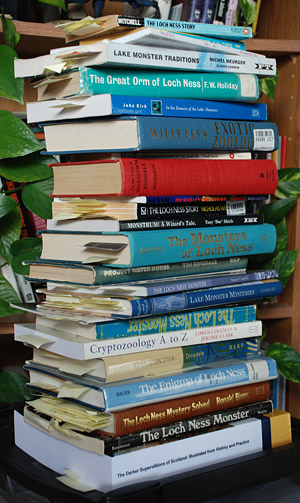

Some of the Loch Ness monster resources I've been digging into

Making Connections

At the moment, I’m busily digging into the Loch Ness monster literature for a book chapter. The challenge is that the literature on Nessie is so enormous (dare I say, “monster-sized”?) that even the most extensive reading must necessarily be incomplete. It’s daunting to realize the key information could always be one resource away. That’s the way it goes: each discovery spawns new questions, leading us deeper, giving us new perspectives on the vastness of our own ignorance. The more we learn, the less we know.

At the same time, the more we learn, the more connections we can make. Different threads of investigation have a way of leaping together and informing each other. (When this happens, I’m always reminded of science historian James Burke’s wonderful Connections series of documentaries and Scientific American columns.)

Finding connections is fun. Although I’ve researched Nessie before (it’s a lifelong interest), I’m happy to say that I’m digging out all sorts of neat stuff. You’ll have to wait for the book for most of that, but here’s a fun tidbit I just learned: it seems that Philip Henry Gosse (whose 1857 book Omphalos: An Attempt to Untie the Geological Knot underlies so much of modern creationist argument) was the guy who first proposed that sea serpent sightings might be explained by surviving populations of plesiosaurs (in his book The Romance of Natural History). Gosse influenced Rupert Gould, who wrote the first and most influential book on the Loch Ness monster. The links between creationism and cryptozoology are many, but I hadn’t realized that the Omphalos guy laid the groundwork for Nessie! That’s hardly smoking gun stuff (Gould discussed Gosse in the 30’s) but I didn’t know it before. Now I do.

Along the way, there are frequently unexpected chance discoveries on other topics altogether. Digging through newspaper archives over the past weeks (several academic portals, and several pay services), I incidentally happened across a wide swath of primary documents on crystal skulls, the Mokele-mbembe, Ogopogo, and other odd mysteries besides. Did you know about this satirical 1827 attempt (PDF) to prove that Napoleon Bonaparte was “nothing more than an allegorical personage”? Neither did I. (I’ll return to the topic of newspaper archives in a future post.)

Large or small, brand new to the literature or news only to us, discovery is a tremendously rewarding feeling. Radford urges us avoid “approaching research as necessary drudgery,” and instead to take pride, even joy, in the process of investigation. And then, every once in a while, the effort pays off big:

Sometimes you’ll find a “smoking gun” fact or document or photograph that proves that everyone is wrong about the topic. I’ve spent many sleepless nights while in the throes of an exciting investigation, my mind racing with the implications of the information I’ve discovered.

I’ve been there. Let me tell you, it’s quite the feeling when pieces of an unsolved mystery (no matter how small) suddenly click into place. For those who care about finding out, there’s a unique joy in finding out first.

"

No comments:

Post a Comment